About

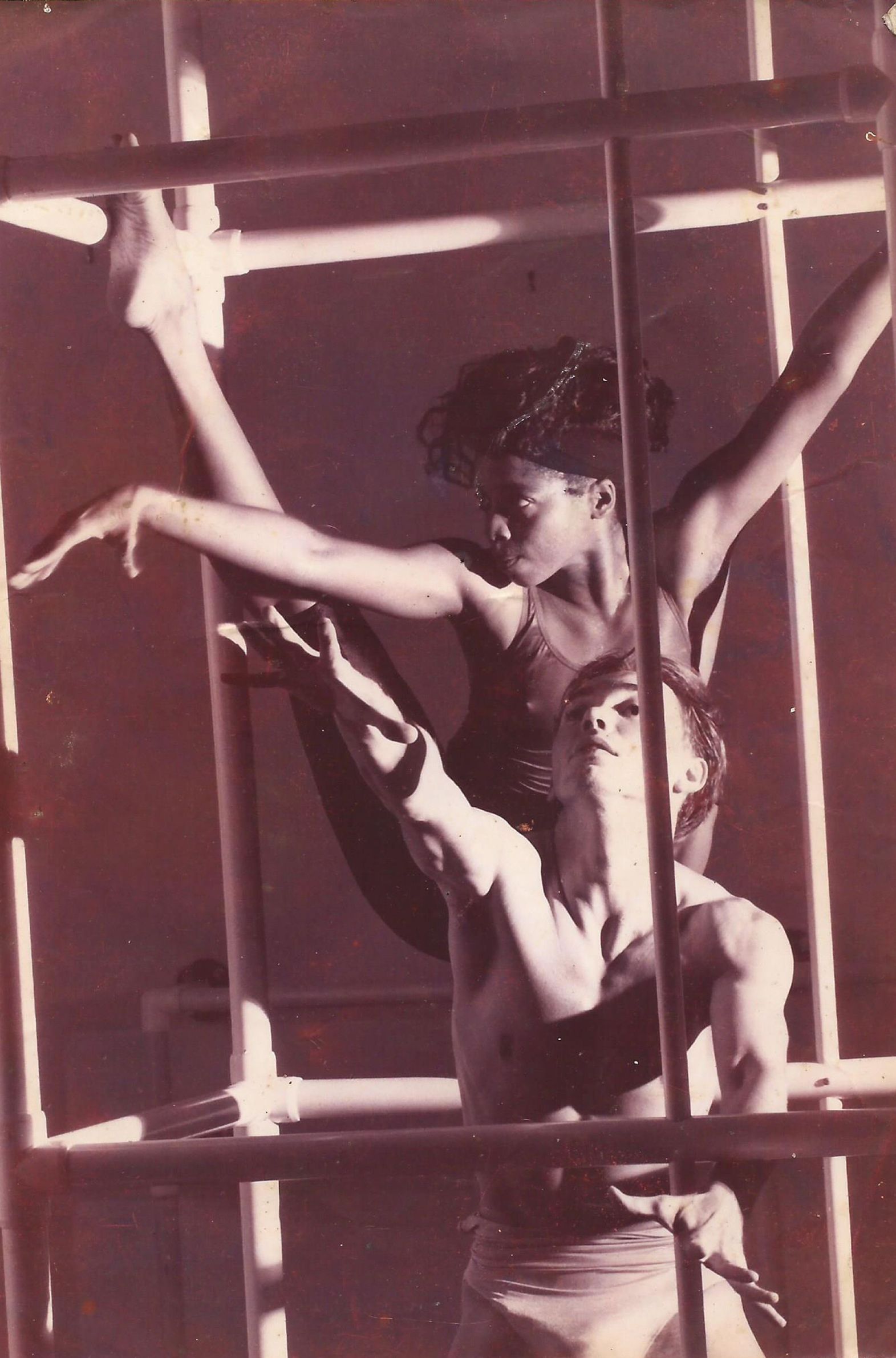

IFE-ILE Dance Company

Born in Havana, Cuba, Neri is a dancer, multidisciplinary choreographer and scholar. She holds an MFA in dance with a minor in film from the University of Colorado at Boulder. She also studied at Instituto Superior de Artes and Escuela Nacional de Instructores de Artes in, Havana. Neri is the founder and artistic director of IFE-ILE Afro-Cuban Dance Company, based in Miami, which repertoire combines traditional and contemporary pieces integrating the Cuban rich expressions. She founded IFE-ILE in 1996 as a response to a perceived lack of representation of Afro-Cuban dances in Miami.

Torres has performed and choreographed worldwide for tours, commercials and films, and also produces the IFE-ILE Afro-Cuban Dance Festival every summer in Miami, FL, since its creation in 1998. Besides, exciting dance workshops and performances, the festival contains an academic conference component that attracts local and international participants and renowned scholars among them the late Dr, Katherine Dunham in 2004. The festival now merged with the Biennial Caribbean International Dance Conference that Neri founded in Barbados in 2014, which aims to make visible and authenticate the contribution of Caribbean dance to universal popular culture through experiential exchange with scholars and practitioners from around the world. In addition, Neri is the main editor of the book “Perspectives on Dance Fusion in the Caribbean and Dance Sustainability: Rituals of Modern Society”, derived from the conference’s proceedings.

During her career, spanning over twenty years, Neri has worked on numerous international tours, movies, television and theatrical productions with renowned artists. She choreographed Gloria Estefan’s Grammy award-winning video No me “Dejes de Querer” and actor Andy Garcia’s directorial debut movie “The Lost City”.

Torres weaves the elements of entertainment, social impact and education into all of the organization’s programs and performances. In addition to its annual festival, IFÉ-ILÉ performs throughout Miami-Dade County and gives interactive, educational workshops at schools, colleges and universities, museums and other festivals and events.

In 2002, Neri was one of the leading Hispanic professionals who were appointed the “Woman of the Year” award by Glamour magazine in Spanish. In 2013, Torres received the State of Florida Folk Heritage Award from Florida Secretary of State Ken Detzner for her significant contributions to Florida’s cultural heritage through her outstanding achievements as a performer and advocate of Afro-Cuban traditional dance. Her company has received two Knight Foundation grant-awards: one in 2015 featured the premiere of Contra Viento y Marea (Under Heaven and Earth), a multidisciplinary piece about the Cuban Mariel boatlift, and in 2017 for Ni de Aquí ni de Allá (Nor From Her, Not From There), featuring dancers from both Cuba and US polarized shores under Neri’s direction.

Neri’s research focuses on focuses on dance and migration, cultural appropriation, the philosophy of embodied spiritual practices, women in dance, multidisciplinary practices and commercialization of traditional dances. Her scholarly work has been presented in several conferences such as National Dance Education Organization (NDEO), Caribbean Studies Association (CSA), Association for the Study of the Worldwide African Diaspora (ASWAD) among other.

HISTORY

Since its creation in 1996, IFE-ILE has been a forerunner promoting Afro-Cuban culture in the US. Our organization continues to be a source of inspiration and a model for many locally and abroad.

IFE-ILE Dance Company is the most renowned Afro-Cuban dance troupe in Miami. Famous for the traditional Afro-Cuban ritual dances, our repertoire includes Reggaeton, Mambo, Rumba, Conga, Chancleta, Son, Salsa, and also boasts contemporary choreographies resulting from the fusion of Modern dance and Afro-Cuban forms.

Our programs help strengthen the reputation of Miami-Dade County as a destination for cultural heritage tourism and the arts. We’re a draw for the growing number of people – locally and worldwide – enchanted by Afro-Cuban culture and eager to learn about and experience it.

We help preserve and cultivate the heritage of Miami’s Afro-Cubans; build bonds and cultural understanding between different communities, organizations and residents; and enhance cultural awareness, pride and opportunities for residents of low-income neighborhoods.

Through our collaboration with government agencies, educational institutions, and local/national organizations, we offer our programs in schools and universities, tourist destinations and low-income neighborhoods of South Florida. Our partners have included, for example, Florida International University, Miami Dade College, Arts for Learning, The Non-Violence Project USA and Viernes Culturales.

In addition to representing Cuba and its vibrant color and tradition, IFE-ILE represents the diversity of Miami itself. We regularly collaborate with other arts, educational and social service organizations that serve the needs of Miami’s various cultural communities (Brazilian, Haitian, Jamaican, Puerto Rican, African-American, etc.). And we reach people from throughout the U.S. through the workshops and events offered during our annual Afro-Cuban Dance Festival.

The company’s most outstanding performances include the Latin Grammy Awards and the Billboard Awards as part of famous Cuban singer Gloria Estefan’s production, Super Bowl Sunday, festivals such as the Smithsonian Institution’s Folklife Festival and the Emancipation Celebration in Trinidad-Tobago. IFE-ILE has also performed in several videos. Commercials and documentaries include “Celia, The Queen”, as well as Andy Garcia’s directorial debut film, The Lost City.

Below is a list of IFE-ILE highlights

- Superbowl, Bayfront Park, 2020

- Art of Black, Koubek Center, 2019

- Havana Mix 2, IFE-ILE 20th anniversary, Miami, 2018.

- Faena Art, Inaugural Procession, 2018

- Video for Amara la Negra, 2018

- Ni de Aqui ni de Alla, (Neither Here nor There). Koubeck Center, Miami, 2017.

- Ciudad de Orichas, Koubek Center, 2016.

- Contra Viento y Marea (Under Heaven and Earth), Miami Dade County Auditorium, 2015.

- In the River of her Eyes, Columbia College, Chicago, 2014.

- Havana mix, Little Haiti Cultural Arts Center, Miami, 2013.

- Flash mob for the Miami International Airport, 2013.

- 1, 000 Random Acts of Culture, Knight Foundation, 2012.

- Hispanic Heritage Month Celebration, City of Doral, 2013

- Cuban Night Show, Global Village, Dubai, EAU, 2011.

- Art of Storytelling, Miami Dade Public Libraries, 2010 – 2014.

- Monday Football, Dolphin vs. Jets, 2009.

- Celia, The Queen, documentary on the life of the late Cuban singer Celia Cruz, featuring IFE-ILE, released 2009

- IFE-ILE Afro-Cuban Dance Festival West in collaboration with the University of Colorado, 2007

- NFL Super Bowl Experience Pre-Game Events and Coach’s Party – 2007

- The Lost City, movie, directorial debut of renowned actor Andy Garcia featuring IFE-LE, released 2006.

- Collaboration with Arts for Learning to bring cultural understanding to underserve communities of children and at risk adolescents 2006.

- Guaguanco, The Rumba Musical, LA, 2004

- Emancipation Celebration Day, Trinidad-Tobago, 2003

- For love or Country: The Arturo Sandoval Story, HBO movie featuring IFE-LE, 2000

- Orange Bowl Parade, Miami, Artistic Director for IFE-ILE performance- 2000

- Latin Grammy Award, Staples Center, Los Angeles, Choreographer – 2000

- Alma Caribena, CBS Press Release, Atlantis, Bahamas, Choreographed by Neri Torres and featuring IFE-ILE

- No me Dejes de Querer, Gloria Estefan’s Grammy awarded video 2000, Choreographed by Neri Torres and featuring IFE-ILE

- Gloria Estefan’s Millenium Concert, American Airlines Arena – 2000

- Guaguanco Oyelo Bien – Musical, Colony Theater, as part of the second annual IFE-ILE Festival – 1999

- Fiesta Africana y Caribena, Colony Theater, as part of the Florida Dance Festival – 1999

- NFL Super Bowl Experience Pre-Game Events and Coach’s Party – 1999

- ILE-ILE’s first Annual Afro-Cuban Fest at BASH-1998

- Caribbean Percussion Traditions in Miami presented by the Historical Museum of South Florida – 1998

- Gloria Estefan’s Evolution World Tour-Europe, Australia, Asia, Canada, Mexico, U.S., Puerto Rico; 1996-1997

- Smithsonian Folklife Festival, Washington DC – 1996.

IFÉ-ILÉ works with a group of 12 dancers and musicians. Below are key musicians in the company.

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. It has survived not only five centuries, but also the leap into electronic typesetting.

BOARD

Gilbert Squires

Claudina Torres

Aileena Ochoa

Kameelah Benjamin

afro-cuban traditions

IFE-ILE performs and teaches a variety of Afro-cuban music and dance traditions, from the sacred and folkloric to the latest popular fusions.

Yoruba and Orisha Traditions

Most of the sacred dances we perform are from the Afro-Cuban religion of Santeria, or Regla de Ocha. Santeria is based on the Orisha worship of the traditional religion of the Yoruba people from West Africa, in what is now southwestern Nigeria and eastern Benin.

Yorubas brought their religion to Cuba during slavery. Nearly 1 million Africans from West and Central Africa were captured by Cuba’s Spanish colonists and brought to Cuba during the 16th through 19th centuries. As Cuba’s plantations expanded in the late 18th and 19th centuries, so did the slave trade. Most enslaved Africans in Cuba were Yoruba, and thus had a significant cultural influence on the Africans of various ethnic backgrounds.

Cuban Orisha Percussion / Batá Drums

Batá drums are a set of three double-headed religious drums used in Cuba: The Iya, Itotele and Okonkolo. Sacred to Yoruba religion and Santeria, they have also been used in secular music such as salsa and jazz.

Percussion is a crucial component of the Orisha religion, in that it is the vehicle through which devotees communicate with the Orishas (deities). For the most important religious ceremonies, an ensemble of three double-headed batá drums is employed and frequently augmented by the acheré (a small gourd rattle). Batá drums are ritually consecrated and are particularly pleasing to the orishas.

In ceremonies where there is a less rigorous protocol, other instruments can be used, such as shekerés (large gourd rattles that are strung with beads or seeds), conga drums and a guataca (a hoe blade or cowbell played with a striker). Orisha percussion generally accompanies singing in which deities are praised and invited to descend upon their devotees.

Though most Orisha percussionists play mainly for religious ceremonies, some occasionally appear in nightclub shows, museum programs or similar settings. Orisha percussionists believe that, when they perform in secular contexts, they help audiences gain a new perspective on a religion that is often misunderstood.

Orisha worship has since spread to Miami and other cities in the U.S. where Afro-Cubans have settled.

Elegguá

The Orisha Elegguá is one of the most respected deities of the tradition. He is the trickster Orisha, represented as a child or an old man, and the owner of all roads, which he can open — or block. As a messenger between humans and Orishas, he must always be honored first at ceremonies and religious events. He loves candy, toys, rum and cigars, and his colors are red, black and white.

Ogún

The Orisha of iron, war and labor, Ogún uses his machete to clear the pathways opened by his fellow warrior Eleggua. A blacksmith, he is a solitary fellow who lives in the forest with his friend Ochosi, the hunter Orisha. He gave humans our tools and technology, and is both destroyer and producer. He likes rum and his main colors are green and black.

Ochosi

Ochosi is the hunter Orisha, who scouts the forest so that a path can be opened and clear by his fellow warriors, Eleggua and Ogun. He helps us focus our attention on our desired goals and results, and shows human the fastest path to our destiny. He is also associated with justice, and is friends with Obatalá.

Oshún

Oshún is popular, beautiful and seductive Orisha of love, wealth, sensuality, fertility and art. She owns the rivers, and loves the color yellow, honey, sweets, pumpkin and champagne. She is both loved and feared, since she has a terrible temper. She renews the process of creation.

Yemayá

The older sister of Oshún, Yemayá is the mother of all, who rules over the ocean and is well-loved by sailors and fisherman. She is the maternal force of life and creation. Fish are sacred to her, and her colors are blue, white and silver.

Oyá

The fiery warrior Orisha Oyá guards the cemetary and rules over the egun or dead. She is also the ruler of the winds, tornados and hurricanes, and wears a skirt of nine different colors. She is a strong protectoress of women and an Orisha of change. Her colors are burgundy and purple, as well as the colors of the sparkle, which she represents as well.

Chango

The warrior Orisha Chango rules lightning, dance and drums, fire and passion. He is the consuming energy of virility, power and passion. He is handsome and very masculine, and loves women and music. He uses a double-bladed axe and his colors are red and white.

Obatala

Obatala is considered to be the father of the other Orishas, the oldest Orisha and the creator of mankind. He is a peaceful and compassionate Orisha, who represents wisdom and clarity. He is also the guardian of those with mental illness, birth defects, drug addiction and alcoholism. His color is white and his ornaments are silver.

Babalu Aye

Babalu Aye is the Orisha of healing and disease. He appears as a sick man with sores and trembling arms and legs. He teaches compassion and responsibility to others, and is often invoked by people suffering from HIV/AIDS and those rejected from society. He likes popcorn and his colors are brown, black and purple.

The painting above is the work of Miami-based Afro-Cuban artist Aruan Torres. The bata drum was handcrafted by Ezequiel Torres.

Traditional Popular Dance

In addition to traditional Afro-Cuban folkloric styles, Cuba is also known for its popular traditional dances such as Son, Cha Cha Cha, Danzon and Mambo.

Danzón

Created by Miguel Failde Pérez in 1879, Danzón is the national dance of Cuba and evolved from Danza. The music structure – A B A B A – consists of an introduction, A, just used for dancers to make acquaintance, flirt or stroll the dance floor. Then a dance section starts (B), to go back to the introduction and repeat the sequence again. The dance style is elegant yet extremely sensual and flavorful; it is danced off the beat and includes square figures.

Son

Son is derived from Cuba’s African and Spanish roots, and is the predecessor of what is now called salsa. Originally rural music that developed as an accompaniment to dancing, it became a popular in Cuba’s urban areas in the 20th century. Eventually, it was adapted to modern instrumentation and larger bands. Traditional Son instrumentation could include the tres (a type of guitar with three sets of closely spaced strings), standard guitars and various hand drums and other percussion instruments. Many sons also include parts for trumpets and other brass instruments, due to the influence of American jazz.

Son, the dance, starts with the formal, closed embrace of the man and woman. The couple maintains a very upright frame, with quick flirtatious and sensual side-to-side movements of the shoulders, torso and hips accenting the underlying six count rhythm of the feet. Son is danced off the beat, so the couple moves on the half beat before one.

Cha Cha Cha

Cha Cha Cha arose in the early ’50s as an offshoot of Danzon and Mambo, and was created by Enrique Jorrin – the original rhythm is onomatopoeia of the sound of the percussion and the one created by the dancer’s feet dragging on the ground. Cha-cha-cha is danced off beat (the dance starts on three quick changes of weight — thus the name cha-cha-cha — preceded by two slow and a pause). It was later adopted and commercialized by ballroom dancers who for teaching purposes (for those unable to identify the beat). A cha was dropped and it became only Cha-cha. In Cha Cha Cha, like mambo and rumba, the dancers’ hips are relaxed, allowing free movement in the pelvic section.

Rumba de Salon/Cuban Ballroom Rumba

Rumba de Salon, or Cuban ballroom rumba, grew from folkloric rumba but with a strong influence from ballet techniques in order to commercialize the style (taking from its intricate hip patterns as created in the black neighborhoods). This already processed Rumba eventually derived into the even more commercialized Ballroom Rhumba version.

Mambo

In the late 1940s, many North Americans — especially those from the East Coast — flocked to Havana, Cuba for their vacations, and the most famous U.S. and Cuban dance bands performed in Havana’s casinos. Orestes Lopez and Israel “Cachao” Lopez created modifications over Afro-Cuban rhythms and particularly the Danzon, creating a new rhythm called mambo infused with American jazz band format. Mambo was danced in the same upbeat and sassy manner as American swing. The word “Mambo” comes from the warriors’ song of the Congo (one of the most important African groups brought to Cuba as slaves during the colonial times) There are two forms of dancing Mambo: single and double tempo.

Fusions/New Styles

The latest craze in Cuba (and Miami) right now is Timba — a blend of Afro-Cuban folkloric music, jazz and even funk and Hip Hop that makes everyone want to move. IFE-ILE also creates our own fusions of the traditional with modern, jazz and popular dance.

Timba & Hip-Hop

Timba was first developed in Cuba in the ’70s, but fully emerged during the ’90s, a widely popular style of popular music and dance. By the mid-’90s most local Cuban dance bands performed timba. It was innovative and fresh — a fusion of popular Afro-Cuban dance with jazz and even funk influences. It was very popular among Afro-Cubans, who were celebrated in its songs, along with Afro-Cuban neighborhoods. But timba also provoked controversy, with its relaxed and irreverent lyrics and aggressive dance moves. It is very much influenced by rumba, and is so enticing to dancers that they may dance until exhausted!

Afro-Modern/Afro-Cuban Modern

Afro-Modern is a fusion of modern dance with West African influences. Afro-Cuban modern incorporates the fundamental moves of traditional and folkloric Afro-Cuban dance.

Salsa & Casino de Rueda

Casino/Rueda is an exhilarating form of Salsa dancing, which some people call Cuban Square Dancing because it involves couples exchanging partners. The term Casino comes from the fact that it started in the 1950s in a Havana social club called El Casino Deportivo, and was brought to Miami by the first wave of Cuban exiles. Over the years, Casino has grown not just in size but also in complexity and style, influenced by disco and later Hip Hop moves. There aredozens of turns, and each has a name and most have hand signals. This form of dancing salsa is popular because of how it connects dancers with each other both physically and mentally.

Congo/Abakua/Arará

Afro-Cuban music is also influenced by African ethnic groups from the congo and arara region, as well as by the all-male society of the Abakua.

Palo/Mayombe

Palo traditions come from the Bantú people of Central Africa (particularly from Congo). The Bantú represent the majority of African slaves coming into Cuba during the 17th and early 18th century; later the Yoruba (from Nigeria) became the primary group brought to Cuba as slaves. Drums and hand rattles are used in this music, which is based upon communication with ancestral spirits, the dead, as opposed to the Orishas. The songs and chants, often in a hybrid combination of Spanish and Bantú words, play a central role in the rituals of Palo. Music of this tradition has had a strong influence on popular music forms like Rumba, Son and Mambo.

Yuka

Yuka is a popular form of secular Congo music that was played during the 19th century and incorporated Yuka drums. Yuka dancing imitates the body language of chickens and roosters, and features the vacunao, a pelvic thrust that is also used in rumba and other dances derived from the Congo.

Abakua

Abakua comes from the Calabar region of West Africa. Its special songs and drums are derived from all-male secret societies. These traditions retain many of the elements of African mystical ritual practice.

Arara

From the Fon people and the Arara kingdom of the Dahomean region, now known as Benin, Arara rhythms, songs and dances were introduced into eastern Cuba through Haiti, where many of those rituals and ceremonies are still practiced.

Makuta

Makuta is a social dance of Congo origin. The makuta drums are a forebear of the conga drums. In Cuba, makuta refers to a festive gathering or a type of ritual staff, which is used at certain moments in Palo ceremonies to strike the ground in a rhythmic accompaniment to a song or dance.

Rumba & Other Folkloric Dance

Afro-Cuban rumba is based on African rhythms and dance moves but with influences from Spanish Gitano/gypsy flamenco dance and song. Other popular folkloric dances include comparsa and carnaval dance, chancleta and yuka.

RUMBA

There are various styles of Afro-Cuban rumba music and dance, but all have strong influences from African drumming and dance and Spanish/Gitano poetry, singing and dance. And in all rumba, the clave beat (2-3 or 3-2) plays a very important role. Afro-Cuban rumba is entirely different than ballroom rumba or the African style of pop music called rumba. Rumba developed in rural Cuba, and is still danced in Havana, Mantanzas and other Cuban cities as well as rural areas, although now it is infused with influences from jazz and hip hop.

The three basic types of rumba include:

Rumba Yambu

This is the oldest known style of rumba, sometimes called the old people’s rumba because of its slower beat. It can be danced alone (especially by women) or by men and women together. Although male dancers may flirt with female dancers during the dance, they do not use the vacunao — the symbolic, sexual “vaccination” — used in rumba guaguanco.

Rumba Guaguanco

Rumba Guaguanco is faster than yambu, with more complex rhythms, and involves flirtatious movements between a man and a woman. The woman may both entice and “protect herself” from the man, who tries to catch the woman offguard with a vacunao — tagging her with the flip of a hankerchief or by throwing his arm, leg or pelvis in the direction of the woman, in a symbolic attempt at touching or sexually contacting her. When a man attempts to give a woman a vacunao, she uses her skirt to protect her pelvis and then whip the sexual energy away from her body.

Rumba Columbia

In this fast and energetic style of rumba, with a 6/8 feel, solo male dancers provoke the drummers to play complex rhythms that they imitate through their creative and sometimes acrobatic movements. Men may also compete with other men to display their agility, strength, confidence and even sense of humor. Columbia incorporates many movements derived from Congo dances as well as Spanish flamenco, and more recently dancers have incorporated breakdancing and hip hop moves. Women are also beginning to dance Columbia, too.

COMPARSA

Cuban comparsa is the dance of the street carnival — and is more commonly known as a conga line. It is loud, flashy and fun, with dancers in colorful and flamboyant attire and musicians playing horns (trumpets, trombones, tubas, etc.), percussion instruments (maracas, bongos, congas, guiros, batas, claves, checkeres, surdos, tamborines) and whistles. In a comparsa some people hold farolas, large and elaborately decorated processional items on long sticks that are usually carried at the front of the parade and twirled or spun by their carriers, in time to the music.